In this Initial Public Offerings (IPO) chapter we will cover six key topics:

- Initial Public Offerings Overview

- Involved Parties

- Listing Considerations

- Valuation Methodologies

- The “Greenshoe” Option

- Registration Statement

Initial Public Offerings Overview

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is the means by which privately held companies transition into publicly traded companies. Hence the phrase, “taking a company public.” From an organizational standpoint, taking a company public is one of the biggest decisions a company’s board of directors will make in the company’s lifetime. The transition from a privately-held entity to a public one has a substantial impact on how the company operates.

An IPO is also one of the most tedious projects an investment banker will work on for a couple of reasons. For one, it requires coordination across a large team of involved parties: the company’s management, the company’s legal counsel, the company’s auditors, underwriters, and the underwriters’ legal counsel will all have a view on issues that impact each participant. This group of stakeholders must reach a consensus on every decision for the process to smoothly progress through each step. Also, the IPO process is tedious because of the vested interest of board members, company management, and company employees. The company’s board and management are likely not acting only as a fiduciary to shareholders, but participating in the process as shareholders too. Thus the board and management have a responsibility to act upon the best interest of all shareholders, but in some situations, this may run contrary to what is best for the board member or management executive individually. This “agent-principal” problem can lead to a lot of possible complications in the IPO process.

Why Choose to “Go Public”?

There are several reasons that companies might decide to undergo an IPO, including:

- Providing liquidity for a parent company or employees: Existing shareholders (generally employees, management, and board members, and often venture capital investors), use an IPO to monetize all or some of their equity stake. Without the IPO, it is often difficult to translate the “paper” value of the shareholders’ equity positions into cash, because it is difficult to sell the positions without a market for trading them.

- Access to the capital markets: Proceeds raised through an IPO are not solely for the benefit of selling shareholders. Proceeds can be used to fund organic growth and expansion, retire existing debt, or expand capacity in other capital markets. All other things being equal, public companies have more financing alternatives available, including bank debt, senior debt, hybrid/mezzanine capital, or equity-linked alternatives.

- Establishing a currency for growth: As stated, public companies have more funding alternatives available to manage operations and growth. One example of this is that publicly traded stock can relatively easily be used as a currency to fund acquisitions without using cash or incurring additional debt. The acquiring company simply exchanges its shares for the equity shares of the company being acquired. This not only fortifies the acquirer’s balance sheet, but also enables the target shareholders to participate in the anticipated upside of the combined company.

- Establishing a transparent value for the enterprise: Following a successful IPO, the company’s board and management team will have a readily available measure with which to determine the value of the company, as well as compare it with that of other companies. Additionally, the board and management can now measure value creation over a defined time period, and compare it to the value creation of peer companies.

- Branding/prestige: A public stock offering potentially strengthens visibility and name recognition for both current and new customers and stakeholders.

IPO Timeline

From start to finish, the IPO process generally takes about four months. This typical time frame includes any organizational structuring, due-diligence processes, legal documentation, investor marketing and pricing, and evaluation of market conditions. There are a few reasons the process could take longer, however.

Given that boards and management teams have a vested interest in maximizing proceeds, both for themselves as well as for the sake of all selling shareholders, market conditions can play a considerable role in determining timing. Directly following a market crash, for example, a company may decide it is not the best time to go public. As a result, in periods of significant market volatility, a substantial IPO backlog can develop. This was the case in the second half of 2008 and in 2009 following the financial crisis.

Additionally, an IPO might get held up by regulatory review. For example, the SEC’s review of the company’s registration statement may result in a large number of comments and changes that need to be addressed before the registration will be approved. This can delay finalizing an effective registration statement and prospectus.

The following graphic displays the various elements of an IPO process, and the timing of those elements under normal conditions:

Involved Parties

Every IPO has a series of parties involved in the process. Investment banks are responsible for underwriting and running the overall IPO process, but the process requires significant input from auditors, regulators, legal counsel, and public relations groups (not to mention the company management itself). Following is a brief summary of the role that each outside party will play in the IPO management process.

Investment Banks

The IPO syndicate group is comprised of investment banks that will serve as either bookrunners or co-managers. The bookrunners lead the IPO process. They perform the majority of the work required to take a company public, and are included in the process from the outset. Co-managers perform a subordinate role—they provide additional distribution of the shares being sold. The co-managers are often specifically selected to reward lending relationships (for example, if the co-manager lends money to the company), or for targeted sales of shares to investors within a specific geographic region.

Bookrunners are referred to as such because they will manage the order book for the company’s securities once the IPO is placed into the market. Bookrunners are also responsible for the following:

- Advising the client on timing of the IPO (from a market opportunity viewpoint)

- Maintaining transparency around any current or future dividend policy

- Organizing and executing the IPO roadshow (a kind of sales tour promoting the shares being sold) during the investor marketing period

- Determining, justifying, and positioning the targeted valuation of the company (i.e., determining share price, and the implied valuation for the company based on that price)

Typically, one bookrunner is named the “lead-left bookrunner” and acts as the lead coordinator in documentation, organization and coordination of the roadshow.

While not acting as legal advisors, the bookrunners are intimately involved in legal drafting and negotiations throughout the process. Each bookrunner should be focused on confirming that the reported financials included in the prospectus agree with the information gathered in the due diligence process, and with the company’s projected financial model (if provided). Equally important, the investment banks are responsible for working with the company’s management to draft the best possible marketing story in the prospectus. The details of the IPO story depend on a company’s industry, but the general structure includes:

- Investment highlights

- Industry overview

- Company description

- Business and product overview

- Management’s discussion and analysis of operating results

- Customer overview

- Company strategy

- Market share opportunities

- Research and product development

- Growth objectives

- Dividend policy

- Consolidated financial data and capitalization

- Management biographies (particularly important in sponsor-led IPOs or high-profile, high-growth IPOs)

Legal Counsel

In an IPO there are two sets of legal counsel involved: one represents the company, and the other represents the investment banks. These advisors are responsible for running legal due diligence, drafting the prospectus, advising on necessary disclosure policy and communicating with the necessary regulatory bodies. Generally, the work will be divided up such that if one set of counsel (say, the company’s legal team) is focused on due diligence or regulatory matters, the other counsel (say, that representing the investment bank consortium) might be responsible for writing the draft of the prospectus.

The underwriters’ counsel acts as an aggregator of information for the bookrunners. It is responsible for collecting, consolidating and communicating the bookrunners’ comments to the company’s counsel on all legal documents related to the offering. The underwriters’ counsel must also provide the underwriters with clean legal opinions (i.e., a 10b-5 filing) and representations and warranties to protect the underwriters from potential frivolous lawsuits (particularly from investors in the stock if the value drops significantly after the IPO).

Auditor

The company’s auditor assists the company in putting financial controls in place, preparing audited and pro forma financial statements, completing accounting due diligence, and providing a comfort letter at the end of the process, confirming the accuracy of the financial information disclosed in the prospectus. The auditor’s role is extensive in aggregating and verifying financial information, but it is not involved in marketing the transaction.

Investor / Public Relations

The company can choose to use an external investor relations team or utilize an internal team to interact with investors prior to and after the roadshow. More often than not, middle-market and large companies have an in-house investor relations group responsible for this important task both during the IPO process and afterward.

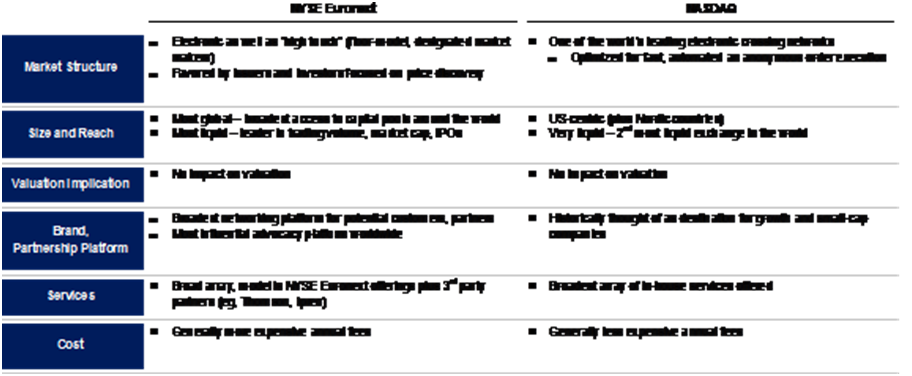

Listing Considerations

U.S. companies generally choose to list their securities for trading on either the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or the NASDAQ stock market, primarily because investors continue to view the U.S. stock market as the global leader in market liquidity. Additionally, investors in a United States–registered IPO benefit from an extensive SEC review and U.S. GAAP accounting safeguards. That said, certain global brands target dual-listed shares to raise capital in multiple operating jurisdictions, and to increase and entrench brand recognition. Recently, companies have targeted developing capital markets because of their growth potential from the consumer sector. A notable example is a series of Hong Kong exchange listings for high-end European fashion and consumer brands.

The NYSE and the NASDAQ share requirements that relate to the board of directors, its audit committee, and its compensation committee. First, NYSE and NASDAQ require that a majority of the board of directors be comprised of “independent” directors (in relation to company management). The size of the board is influenced by this requirement, which will either limit management’s presence on the board or result in the inclusion of additional independent directors. Second, a public company must have a three-member audit committee composed entirely of independent members, which is defined both by reference to NYSE or NASDAQ rules, as well as Section 10A of the Securities Exchange Act. The audit committee must have at least one “financial expert,” and all audit committee members must be “financially literate.” Finally, NYSE requires that listed companies have a compensation committee and a nominating/corporate governance committee, each composed entirely of independent directors. The NASDAQ requirement is very similar, but slightly more flexible, in that compensation decisions and nominations may be made by a majority of the independent directors of the board – not a defined committee.

Valuation Methodologies

Trading Multiples: Comparable Companies and Precedent Transactions

IPOs are generally marketed and priced on a per-share trading multiple basis, with comparisons drawn between a company’s multiples and those of public operating peers and recent similar IPOs. Investors generally choose trading multiples over a discounted cash flow analysis (DCF) because a DCF can be inaccurate when there is little or no dividend payment history; there can also be uncertainty as to when a dividend might be instituted.

Most companies avoid instituting a common dividend at the time of an IPO for two reasons. First, once a dividend is instituted, the market will usually expect the company to consistently pay a quarterly dividend on an on-going basis (and may even have hopes for dividend increases). Second, a large number of companies undertake an IPO specifically to raise capital to fund growth opportunities, not to distribute capital to its investors. Instituting a dividend would run counter to this strategy.

The appropriate reference trading multiples to be used for IPO valuation vary by industry, but as a frame of reference, investors generally focus on cash flow or book value-based multiples. For example, consumer & retail company investors typically use Earnings Before Interest, Tax and Depreciation & Amortization (EBITDA) as a proxy of Free Cash Flow, while for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and utility companies, Funds From Operations (FFO) is generally used. Investors focus more on book value or tangible book value per share for financial institutions, particularly for banks and insurance companies.

The multiple at which an IPO prices is commonly referred to as the IPO multiple. The IPO multiple, as compared to public peers, is usually discounted given the risk profile of a new issue. This discount is referred to as an IPO discount, and usually ranges from 10% to 20% from the average/median peer, depending on a company’s industry and growth outlook.

Discounted Cash Flow/Merger Analysis

When a company is evaluating which investment banks to select as bookrunners on its IPO, the valuation framework will be more extensive. In addition to the trading multiple valuation, most investment banks will attempt to provide an opinion for the company’s value using either precedent merger transactions or DCF analysis. The analysis will attempt to value the entire company, forming a basis for the value of the new shares being offered (this is based on the target IPO size, share structure for insiders, and the number of new shares to be issued).

Given that most companies undergoing an IPO do not commence paying dividends right away, a DCF analysis will use Free Cash Flow or Free Cash Flow to Equity (i.e., net of interest and preferred dividends). As discussed earlier in this training module, the difficulty with DCF analysis is the sensitivity of the calculated value to the assumptions used (especially the growth and discount rates). Therefore if a DCF analysis is to be used, it is important to be rigorous about the rates used for both.

Merger analysis will generally use a similar benchmark as trading multiples—cash flow or book value—but not on a per share basis. For example, it is common practice for investment banks to evaluate the value of a company on the basis of the EBITDA/Enterprise Value multiple. Using an observable EBITDA/EV multiple enables the company to determine an implied value for the entire company, which can be used to determine the value of the equity held by common shareholders (once net debt, minority interests and preferred stock are subtracted out).

The “Greenshoe” Option

When an IPO prices, the bookrunners will generally sell more shares than the company actually issues—in other words, they will overallocate the offering. This results in the bookrunners being in a “naked short” position—the bookrunners will need to purchase shares in the company from others in order to be able to deliver all of the shares promised to buying investors. Doing so provides some support for the stock in the secondary market with low risk to the bookrunners. In order to prevent the bookrunners from taking losses in the event that the shares rise, the issuing company will implicitly issue the bookrunners a call option known as the greenshoe option. Here’s how it works.

In the event that the shares do not trade at a higher price when free trading begins, one of the bookrunners will step into the market, buy back the number of shares overallocated to investors, and thereby cover the bookrunners’ short position. This supports the price of the stock by creating a demand in the marketplace (the bookrunners buying shares) without exposing the bookrunners to a long position in the stock after having bought these shares. (The bookrunner responsible for this important task of covering the short position is commonly referred to as the stabilization agent.)

If instead the stock trades up after freeing the syndicate, the greenshoe option kicks in, preventing the bookrunners from losing money on their short position in the company’s shares. The greenshoe option allows the stabilization agent, after the deal prices and public trading begins, to purchase up to a pre-specified percentage of the number of shares issued (15% is a commonly used figure) at the issue price, less the applicable underwriting fees. This option typically expires 30 days after the date of the IPO. By holding this option, the stabilization agent avoids the risk of having to purchase shares in the open market at a high price to cover the bookrunners’ short position if the stock price increases; this protects against the bookrunners taking a principal loss.

If the greenshoe option is exercised, the company issues additional shares and receives additional proceeds; thus, if the option is used, the IPO deal size grows. If the option is not exercised, the bookrunners will use proceeds from the overallotment (short position) to buy shares in the secondary market, and the company will receive no additional proceeds.

Regardless of whether the option will be exercised, investors prefer to have a transaction structured to include a greenshoe option. The option provides confidence that the issue will be properly managed, because bookrunners are incentivized to support the stock price in the secondary market directly after the IPO. This will help reduce the possibility of share price volatility in the days after the IPO begins trading.

Registration Statement

The IPO registration statement, which like all registrations for the public sale of securities is submitted to the SEC under Form S-1, is prepared by legal counsel and company management and has two main parts. Part I is the prospectus—the legal document used to describe the company and sell shares. Everyone who is solicited to potentially buy the IPO shares must have access to the prospectus. Part II includes additional information that the company does not have to present to investors by law. However, all of the statement (both parts) are filed and available on the SEC website.

An excellent overview of the Registration Statement can be found at Inc.com.

We recommend that all current or prospective investment banking analysts look at recently filed S-1’s to garner a detailed understanding of the information included in a company’s registration statement and how it is typically presented to investors. Generally, an effective registration statement will include the following items:

- Historical and Interim Financial Statements, including relevant footnotes

- At least two full fiscal years of a company’s Balance Sheet (audited)

- At least three full fiscal years of a company’s Income Statement (audited)

- Interim (year to date) Financial Statements, (unaudited but reviewed)

- Reporting on company performance by business segment

- Earnings Per Share analysis

- Disclosure on stock-based compensation practices

- Company capitalization and the resulting dilution from the IPO

- Description of the anticipated use of proceeds

- Description of resulting reorganization, if any (e.g., from LLC to C-Corp or Publicly Traded Partnership)